Aug 17, 2017

By Janet Ready, Instructor

I grew up in a small resource-based town on Vancouver Island. My dad was a logger. I’m the oldest of four kids and for most of my life we were on (or just above) the poverty line. I have great memories of love, family and adventures growing up. And a strong sense that I don’t need a lot to be happy. Most importantly I haven’t forgotten where I came from and the values that I learned growing up in that environment.

Public Recreation in Canada has a fascinating history. It started as a social movement to create social change for children living in poor conditions. Community leaders saw it as a way to improve physical and moral development and to build social connections and community. It was a grassroots movement where the National Council of Women played a key role in advocating for safe spaces for children to play as an alternative to crime and gang violence.

Currently Recreation in Canada is seen as a Public Good -- but some argue that we have moved beyond that :

Through much of the 20th century, public recreation was regarded as a “public good.” The emphasis was on accessibility for all, outreach to disadvantaged groups and a belief in the universal benefits to the whole community, not just to users. In the 1990s, recreation departments and organizations came under increasing pressures for cost recovery and revenue generation, including increases in user fees. The community development and outreach functions that were historically part of the mandate of public recreation were often quietly marginalized, as the field shifted its focus to meet the demand from that portion of the population who could pay. Leaders in recreation have continued to stress the need for equitable recreational experiences for all, with a call for the renewed importance of public recreation’s historic mandate of addressing the inclusion of vulnerable populations. Quality recreation needs to be available to all, paid for by a combination of taxes and flexible user fees, which take into account economic circumstances. This does not mean denying services to people who have resources, but that they should not be served to the exclusion of those who face constraints to participation. (A Framework for Recreation in Canada 2015, p 18)

It is worth it to look back at the beginning of the recreation movement to see where we came from in Recreation and what values created this social movement. The Playground Movement is seen as the start of public recreation in Canada.

The Playground Movement

In their text, “Recreation and Leisure in Modern Society”, McLean and Hurd say:

To understand the need for playgrounds in cities and towns, it is necessary to know the living conditions of poor people during the late 1800’s. Urbanization was increasing due to immigration to the United States and Canada. In New York, nearly five of the six of the city’s 1.5 million residents living in tenements in 1791. Social reformers of the period described these buildings as crowded with dark hallways, filthy cellars and inadequate cooking and bathroom facilities. In neighborhoods populated by poor immigrants there was a tremendous amount of crime, gambling, gang violence, and prostitution. (p. 64)

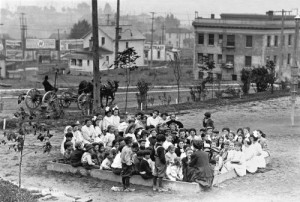

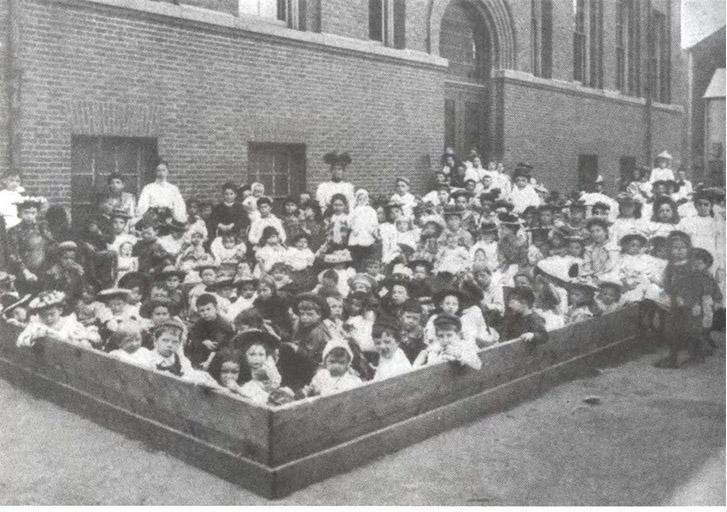

Within poor working-class neighborhoods, there were few safe places where children could play. The Boston Sand Garden (1886) is marked as the beginning of the Public Recreation Movement in the United States. It was the first playground in the country designed specifically for children. “A group of public-spirited citizens had a pile of sand placed behind the Parmenter Street Chapel in a working-class district. Young children in the neighborhood came to play in the sand with wooden shovels. Supervision was voluntary at first, but by 1887 when 10 centres were opened, women were employed to supervise the children. Two years later, the city of Boston began to contribute funds to support the sand gardens. So it was that citizens, on a voluntary basis, began to provide play opportunities for young children.” (McLean and Hurd p. 65)

George Karlis, in his text, “Leisure and Recreation in Canadian Society” says, “At the close of the nineteenth century, perhaps the most important development for leisure and recreation was the establishment of the National Council of Women in 1893. The National Council of Women played a leading role in the development of the Playground Movement in Canada and in examining youth and leisure recreation issues. Its goal was to promote the social welfare role of play and, more specifically to encourage community leaders to establish playgrounds and sand gardens as aids to help build the social and moral character of children.” (P. 46)

Canada’s fist playground was established in Saint John in 1906. Around the same time, Regina, Vancouver, Winnipeg, Ottawa, Hamilton, Toronto, and Montreal all showed initiative in establishing playgrounds signaling the start of the Playground Movement in Canada. The rationale behind the movement was that playgrounds provided social and health benefits, as well as places to play in crowded cities. (Karlis p. 47)

There is a lot more to the story of how Public Recreation grew in Canada – and today we have moved far beyond playground services -- but the Playground Movement is key in looking at where we came from. This movement embodied the values of community development, outreach, equitable recreation experiences for all, and inclusion of vulnerable populations. Does public recreation today embody those same values? Does our work reflect where we came from?

It is important to note that the YMCA and Boys and Girls Clubs were significant organizations in the growth of Recreation in Canada – and are connected on the timeline and events of the Playground Movement. It is worth it to read their specific histories to see how the visions of what recreation could do (and be) for Canadian society grew together.

And no history of Recreation would be valuable without acknowledging that it pre-dates Confederation. “In fact, the first accounts of leisure and recreation and physical activities can be traced back to the Inuit and the Aboriginal peoples of Southern Canada.” (Karlis p. 41). “Traditionally, all aspects of life were integrated for the Inuit and Aboriginal peoples. The activities and experiences of work, play, leisure, recreation, and religion were all interconnected. Physical fitness was an important part of survival, and value was placed on the relationship between mind, body, and spirit.” (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996).

For Specific Histories of the YMCA and Boys and Girls Clubs, check out:

Boys and Girls Club

https://www.bgccan.com/en/AboutUs/OurHistory/Pages/default.aspx

YMCA

http://ymca.ca/en/who-we-are/history/ymca-milestones.aspx

For more information on the history of the Parks, Recreation and Culture Sector in Canada and British Columbia

http://www.bcrpa.bc.ca/about_bcrpa/documents/TheWayForward/AppendixA-HistoryOfTheParksRecreationAndCulturalSector.pdf

References

A Framework for Recreation in Canada 2015: Pathways to Wellbeing. Retrieved June 22, 2017 from http://lin.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/framework-for-recreation-in-canada-2016.pdf

Karlis, George. An Introduction Leisure and Recreation in Canadian Society. Third Edition. 2016. Thompson Educational Publishing, Inc.

McLean, Daniel and Amy Hurd. Kraus’ Recreation and Leisure in Modern Society. Ninth Edition. 2012. Jones & Barlett Learning. Sudbury, MA.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. 1993. Canada: Ministry of Supply and Services.