Biology instructor Kyra Janot, working with five of her students, is researching local seaweed species to help measure future changes in the organisms and their surrounding ecosystems. Janot's research is funded in part by a $56,573 grant from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), received in June 2022, and also by the Applied Research Centre’s ARC Release program.

Ecological Chain Reaction

The project – part of the DFO's Coastal Environmental Baseline Program – is mandated to support the collection of baseline data in certain areas, including the Port of Vancouver. Baseline data provides a snapshot of the state of an area at a particular point in time, against which future data can be compared to monitor how things are changing.

“The last few years have seen some extreme weather events such as heat domes that have likely impacted the health of intertidal organisms such as seaweeds,” says Janot. “With climate change, we could begin to see species shift seasonally, not just annually. Seaweeds could start appearing earlier than normal, for example, or perhaps die off earlier than they otherwise might if temperatures become too hot in the summer.”

Much like plants on land, seaweeds provide food and shelter for numerous other organisms in the marine environment. Changes in seaweed life cycles could have significant impacts on local ecosystems. Janot's and her team’s work will allow scientists to better understand future changes in both the seaweeds and the biological communities they support.

On the Coast

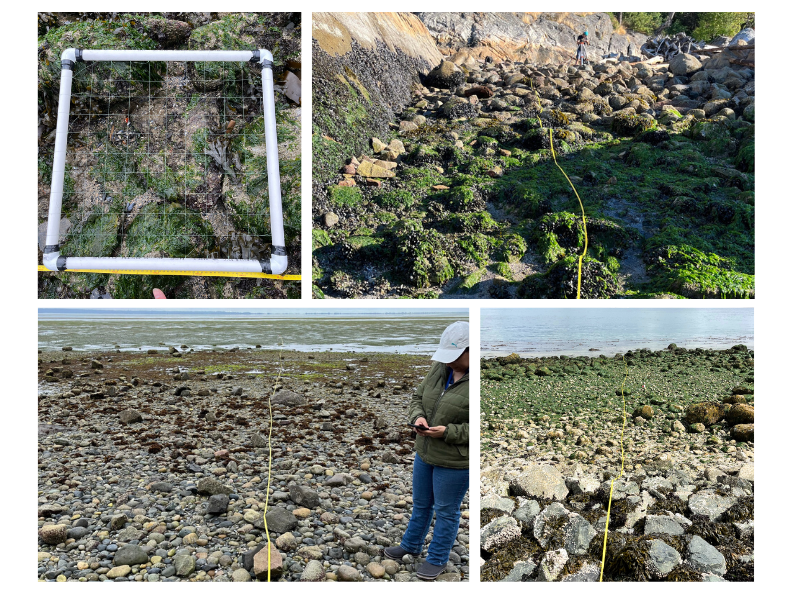

Janot's research involves spending a significant amount of time in the field and often, in the dark. She conducts surveys by visiting a site at low tide where she will quantify and identify different species of seaweed that are present at different tidal heights.

“These kinds of surveys are time consuming and doing this work in the intertidal zone means having to time work with the lowest of low tides,” explains Janot. “This is logistically challenging, especially in the fall and winter when good low tides tend to occur after dark.”

During spring 2023, Janot completed her third and final set of surveys at four separate sites:

- Cates Park in North Vancouver

- Lighthouse Park in West Vancouver

- Brockton Point (Stanley Park) in Vancouver

- Crescent Beach in Surrey

Collectively, these sites overlap with traditional territories of the Tsawwassen, Musqueam, Tsleil-Waututh, Katzie, Squamish, Semiahmoo, and Kwantlen First Nations. The Katzie, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations have all expressed interest in seeing the data when the project is completed.

Next Steps

To fill in the gaps between the snapshots she has taken of the sites via field surveying, Janot has also collected monthly environmental samples from each site. DNA has been extracted from the samples and will be examined for microscopic amounts of tissue or cells.

“Seaweeds and other organisms shed cells and small tissue fragments into the water, so the hope is to extract and amplify the algal DNA specifically to see what might be there and wasn’t visible in the field due to high tide or darkness,” says Janot.

This work will be done using new technology called a minION and a bioinformatics pipeline. If successful, Janot will compare what is found in the water with what she and her team saw in person.

She adds, “If fewer species are detected in environmental samples than in surveys, it will suggest that surveys might be better for identifying how many species are present, despite having to deal with tide times and labour intensive methodology. If the water samples are comparable or better in terms of the species that show up, that will mean it is a reasonable alternative for detecting species diversity year-round.