Mar 15, 2013

Drama of Perception

Stephanie Aitken | Katie Lyle | Shelley Penfold

Curated by Sandra Meigs

Opening Friday, March 15, 7pm

Looking at a painting, what do you expect? Do you know everything a painting can do? What do you want from it? What do you hope for?

There is a fragment of a Goya mural at the Prado Museum in Madrid, Dog half-submerged, 1821-1823, from his Black Paintings. A dog’s head peeks up from a vast mound of brown earth and looks forward to something outside the canvas. It is a small piece, 131cm X 79cm. The small stubby dog head grabbed me from a distance even though I could not really make out what it was. Once I went closer, I was mesmerized by his very strong and enigmatic presence. Something very present yet very fleeting, it portrays a moment of inevitability and fragility of existence. The painting seemed to form before my eyes as if it depicted the fuzzy line between imagination and reality.

When I look at the works of these three painters, Stephanie Aitken, Katie Lyle and Shelley Penfold, I have total conviction that the forms in the painting exist in the world, these forms that have been conjured out of imagination. At the same time, I doubt. Because these fictional forms convince me, I begin to doubt the world and my entire understanding. These paintings cause me to doubt my perception. I look. I have a visual experience for half a second, and then my mind tumbles on to another visual experience. This is why the paintings join me with the world. As I persist in doubt and knowingness, I am closest to my living perceptual experiences of the world.

My mind constructs and reconstructs what I think I see. What appears before me is not really what it appears to be. I feel like the paintings need me. Thus, I am important. The paintings breathe into me, not oxygen, but other physical elements of the world…strange and unusual colours, slippery fields, boundaries and shapes I have not known in the world enter into me through my perceptions.

There is a kind of looking other than that of me looking at paintings: the looking of the painter at the paint and canvas as she paints. This is looking, not outwardly to the world, or to a finished work as I described above. Rather it is looking at the unfolding and the outcome of one’s infinitively minute or extraordinarily grand gestures, tools, paint materials and mixings, ideas, accidental movements, and all the knowledge and skill imbedded in the painter’s brain.

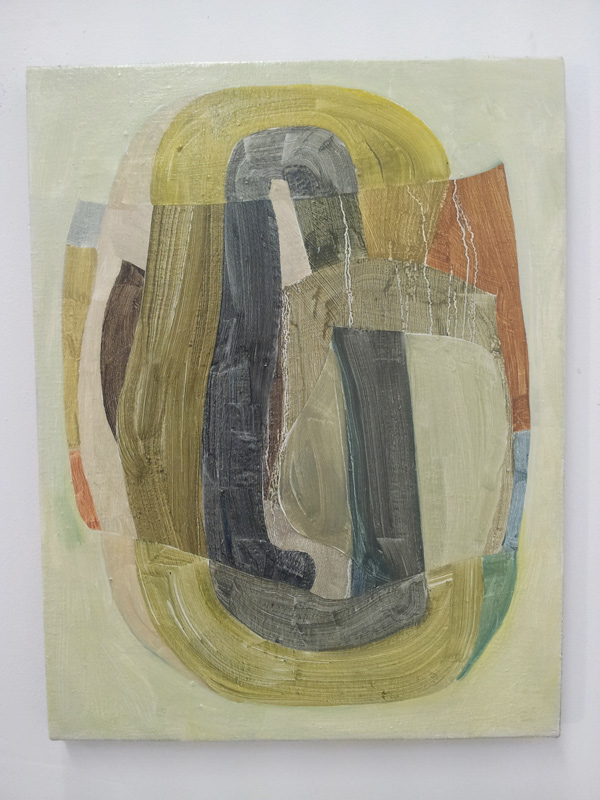

Stephanie Aitken has worked through a series of paintings that are highly layered organic constructs. They seem to have structures deep inside the forms. They seem to have voices of Tenor. The forms fall apart as they come together. The newer work has a thinner handling of paint, as if the paint could dissolve with one’s looking. Aitken has constructed totemic-like jewels that sit at rest symmetrically within the borders of the canvas. They too seem to have a voice, this time a soft soprano, like a young girl.

Who are these oval characters that I see? In some ways they echo the women of Katie Lyle’s work that we also see here in the gallery. And too they echo the drumming of Shelley Penfold’s uncertain and doubtful joyful fields.

Katie Lyle paints young women who seem to be posing for movie star shots. They are small in scale. Their heads fill the canvas and seem to rush to the borders so that they can give no space in which your eye can dwell. The poses demand that you try to capture their gaze, yet you cannot. They are forever, not only aloof, but also unreachable. Plus, you cannot be sure just how that face exists. How can she be like that? And why is there a great darkness around her nose? Has the mouth been blotted out, or is it only trying to speak? Is that a hat or is it her hair? What a weird hairstyle—if that is what it is. She is lit with the light from an old television, or perhaps it is the light of a cheap fluorescent bathroom fixture. You keep on looking and there is always something different there. Then you begin to think the painting might have been purchased at a thrift store, that it is the bad work of an aspiring amateur. And then the breathlessness you feel from its beauty, which practically knocks you out. Lyle will work these small portraits over again and again, sometimes for a year, until she thinks she has it right. Right enough to create this doubt.

Shelley Penfold’s painting has so little structure, so much sheer breath, that one cannot understand it physically. What matter has been acted upon it? She throws paint, puts the canvas in fires, traps it underground, tramps on it, leaves it out in the rain, and only after feeling the canvas has been taken to the edge, where she cannot know its possible beauty (or its possible disinterestedness, for that matter), does she put it up in the studio to ponder. It is like getting to know a toddler who makes jerky movements and utterances, like the strange voice of an unknown language that the painter herself has created. Shelley then works with the hand of a kind of Supreme Being, a person with the light and language of visual structures. If her paintings do not live up to a promised unfolding, they are left to settle at another time, perhaps. If they do unfold, Penfold will steam and smooth the tattered canvas, to make it pristinely smooth and presentable, like one would a crumpled ball gown.

Do we look AT the world? Or do we look INTO the world? Do we know the world inwardly, as if the membrane of our body is permeable to that which is outside of it? Do you doubt what you see? Do you ever fall completely into and beyond what a painting brings to your perception? One should hope for that moment that knows beyond words.

Stephanie Aitken | Katie Lyle | Shelley Penfold

Curated by Sandra Meigs

Opening Friday, March 15, 7pm

Looking at a painting, what do you expect? Do you know everything a painting can do? What do you want from it? What do you hope for?

There is a fragment of a Goya mural at the Prado Museum in Madrid, Dog half-submerged, 1821-1823, from his Black Paintings. A dog’s head peeks up from a vast mound of brown earth and looks forward to something outside the canvas. It is a small piece, 131cm X 79cm. The small stubby dog head grabbed me from a distance even though I could not really make out what it was. Once I went closer, I was mesmerized by his very strong and enigmatic presence. Something very present yet very fleeting, it portrays a moment of inevitability and fragility of existence. The painting seemed to form before my eyes as if it depicted the fuzzy line between imagination and reality.

When I look at the works of these three painters, Stephanie Aitken, Katie Lyle and Shelley Penfold, I have total conviction that the forms in the painting exist in the world, these forms that have been conjured out of imagination. At the same time, I doubt. Because these fictional forms convince me, I begin to doubt the world and my entire understanding. These paintings cause me to doubt my perception. I look. I have a visual experience for half a second, and then my mind tumbles on to another visual experience. This is why the paintings join me with the world. As I persist in doubt and knowingness, I am closest to my living perceptual experiences of the world.

My mind constructs and reconstructs what I think I see. What appears before me is not really what it appears to be. I feel like the paintings need me. Thus, I am important. The paintings breathe into me, not oxygen, but other physical elements of the world…strange and unusual colours, slippery fields, boundaries and shapes I have not known in the world enter into me through my perceptions.

There is a kind of looking other than that of me looking at paintings: the looking of the painter at the paint and canvas as she paints. This is looking, not outwardly to the world, or to a finished work as I described above. Rather it is looking at the unfolding and the outcome of one’s infinitively minute or extraordinarily grand gestures, tools, paint materials and mixings, ideas, accidental movements, and all the knowledge and skill imbedded in the painter’s brain.

Stephanie Aitken has worked through a series of paintings that are highly layered organic constructs. They seem to have structures deep inside the forms. They seem to have voices of Tenor. The forms fall apart as they come together. The newer work has a thinner handling of paint, as if the paint could dissolve with one’s looking. Aitken has constructed totemic-like jewels that sit at rest symmetrically within the borders of the canvas. They too seem to have a voice, this time a soft soprano, like a young girl.

Who are these oval characters that I see? In some ways they echo the women of Katie Lyle’s work that we also see here in the gallery. And too they echo the drumming of Shelley Penfold’s uncertain and doubtful joyful fields.

Katie Lyle paints young women who seem to be posing for movie star shots. They are small in scale. Their heads fill the canvas and seem to rush to the borders so that they can give no space in which your eye can dwell. The poses demand that you try to capture their gaze, yet you cannot. They are forever, not only aloof, but also unreachable. Plus, you cannot be sure just how that face exists. How can she be like that? And why is there a great darkness around her nose? Has the mouth been blotted out, or is it only trying to speak? Is that a hat or is it her hair? What a weird hairstyle—if that is what it is. She is lit with the light from an old television, or perhaps it is the light of a cheap fluorescent bathroom fixture. You keep on looking and there is always something different there. Then you begin to think the painting might have been purchased at a thrift store, that it is the bad work of an aspiring amateur. And then the breathlessness you feel from its beauty, which practically knocks you out. Lyle will work these small portraits over again and again, sometimes for a year, until she thinks she has it right. Right enough to create this doubt.

Shelley Penfold’s painting has so little structure, so much sheer breath, that one cannot understand it physically. What matter has been acted upon it? She throws paint, puts the canvas in fires, traps it underground, tramps on it, leaves it out in the rain, and only after feeling the canvas has been taken to the edge, where she cannot know its possible beauty (or its possible disinterestedness, for that matter), does she put it up in the studio to ponder. It is like getting to know a toddler who makes jerky movements and utterances, like the strange voice of an unknown language that the painter herself has created. Shelley then works with the hand of a kind of Supreme Being, a person with the light and language of visual structures. If her paintings do not live up to a promised unfolding, they are left to settle at another time, perhaps. If they do unfold, Penfold will steam and smooth the tattered canvas, to make it pristinely smooth and presentable, like one would a crumpled ball gown.

Do we look AT the world? Or do we look INTO the world? Do we know the world inwardly, as if the membrane of our body is permeable to that which is outside of it? Do you doubt what you see? Do you ever fall completely into and beyond what a painting brings to your perception? One should hope for that moment that knows beyond words.

– Sandra Meigs, Dec 2012